8.09.21

Do you know that PLR/ELR does not currently apply to digital formats of your books? Read our article on Digital Lending Rights, and why it's important for you as a creator.

Authors and illustrators should be familiar with the public lending right (PLR) and educational lending right (ELR) payments that land in your bank accounts in June each year. PLR / ELR payments are intended to compensate creators for lost royalties when your physical print books are held in libraries and made available to the public to borrow for free.

The ASA has a proud tradition when it comes to PLR / ELR. We successfully campaigned for the introduction of PLR in 1975; we successfully campaigned for ELR in 2000 and now we are campaigning again, this time for the modernisation of those schemes to include digital formats; which we’ve colloquially dubbed ‘digital lending rights’ (DLR).

Here’s a refresher on the Australian lending rights schemes and an explanation of what we are calling for and how you can help.

Who is eligible for PLR / ELR payments?

How are payments calculated?

Payments are determined by the estimated number of copies of your books held in lending libraries in Australia (based on survey data), NOT the number of times your books are loaned out to library patrons.

In 2020, eligible creators were paid $2.18 per book held in libraries and publishers were paid 55 cents per book.

How much is paid out per year?

PLR / ELR payments are the main way the federal government supports and invests in Australian writers and illustrators. The payments are administered by the Office for the Arts and around $22 million is paid out each year, with about 17,000 payments made to creators and publishers.

Over the last five years, over 4,000 new books have been registered for lending rights each year.

What does the ASA want to change?

PLR and ELR payments apply ONLY to print books held in libraries…not to digital formats: ebooks and audiobooks.

We want the Government to expand the eligibility criteria to include digital formats. In our view, a lending rights payment should be ‘format neutral’ and apply whether a book is borrowed in print, ebook or audio format. In this way, the schemes are future--proofed.

We are also asking for a corresponding increase to the PLR / ELR budget in recognition of the fact that the number of eligible creators will increase.

Why expand the eligibility criteria to include digital formats?

The ASA is campaigning for the expansion of the PLR / ELR schemes to include digital formats because:

What do authors say?

In 2020, the ASA conducted a national survey of writers and illustrators, attracting over 1,400 respondents. Of those who receive PLR/ELR, 78.89% of respondents indicated they consider PLR / ELR payments highly valuable.

Authors tell us again and again how beloved the lending rights schemes are. We are told that PLR / ELR payments endure for far longer than the initial spike of royalties upon a book’s release. If a book has found its way onto library shelves, PLR / ELR payments can be among the most stable payments received by an author over a very long time, in an otherwise financially precarious career.

Of those respondents who expressed a view, 99% were in favour of expanding the PLR and ELR schemes to cover digital formats (ebooks and audiobooks).

Have any other countries included ebooks and e-audiobooks in their PLR scheme?

What’s the hold up then?

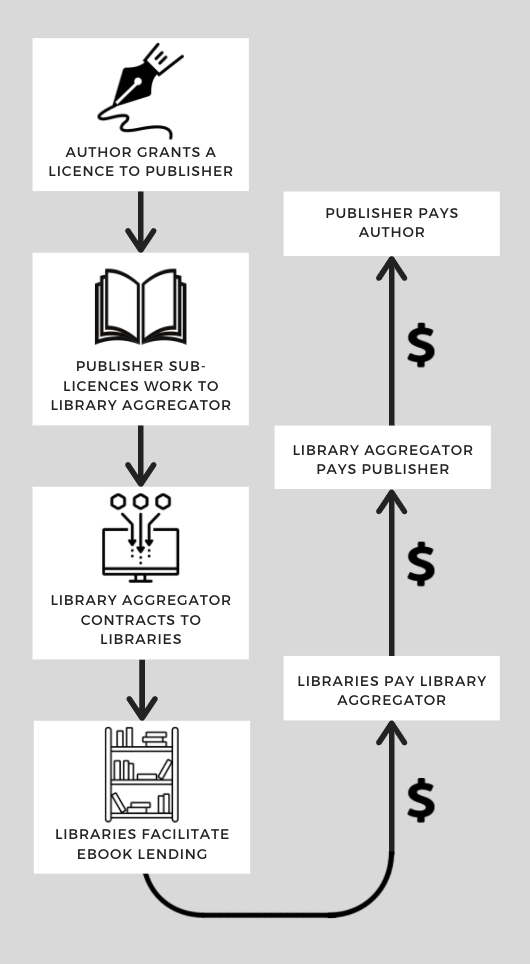

Modernising PLR / ELR requires legislative change. Apart from persuading government this should be made a priority, the greatest difficulty for change is interrogating the existing commercial arrangements, given the considerable complexity in the way that ebooks are licensed to libraries.

Authors are paid under the net receipt royalty rate for digital sales that is specified in their publishing agreement (typically 25%), which are usually reported under eBook sales on their royalty statements. (As best as we can tell, very few Australian publishers separate out ebook library revenue from general ebook sales in royalty accounting statements.)

To the best of our knowledge, when licencing to a library aggregator, trade publishers usually specify “non-concurrent use” in their licence terms, meaning that only one reader can borrow the ebook at any time, just as only one reader can borrow a print book at once. Publishers will set expiration terms for the ebook licence: either after a certain number of loans (which might be 36 or 52) or after a certain period of time (which might be 2 years). At that time, the library will need to refresh the licence and pay for the ebook again if it wants to keep the ebook in its collection. This reflects what happens in the print world when a book becomes dog-eared and tattered after a couple of years of being loaned out (particularly if it’s popular). The print book then needs to be replaced by the library if it wishes to keep the title in its collection.

While the detail of the licence terms granted by publishers varies so there isn’t consistency across the industry, in our view the digital world generally mimics the print world. Accordingly, the policy rationale behind PLR / ELR is equally relevant in the digital world.

How can I help?

The Australian Society of Authors has been campaigning for DLR, communicating with the Minister for the Arts, and raising the issue at federal inquiries and industry roundtables, but we need your help.

Please support the ASA’s campaign by:

Go online and look at your local libraries’ collections and research how many of your titles are available for borrowing in print format? And how many in ebook format? Report this information back to the ASA

Keep up-to-date with ASA advocacy, support and advice

with our fortnightly newsletter.